“I don’t think Dad realised, when he originally started this battle, what responsibility this actually meant for him, personally.”

The broken promise of the Nelson Tenths has had a profound impact on generations of Te Tauihu whānau. What may be the oldest property claim in Aotearoa, the 180-year battle to make the Nelson Tenths whole has taken a devastating toll – not just on the original customary Māori landowners, but on their tamariki, mokopuna and ngā mokopuna nui.

For many of the thousands of descendants of the original owners of the Nelson Tenths estate, their lives have been shaped by this fight for justice.

As the eldest child of Kaumātua Rore Stafford, Brandi Stafford has grown up with the dissonance. Not only is her father currently representing the customary landowners as the plaintiff versus the Attorney-General in the Wellington High Court, but at the age of 83 he has now been championing the struggle for half his life.

“I don’t think Dad realised when he originally started this battle, putting in the Waitangi Tribunal [Wai 56] claim with Hohepa Solomon in 1986, what responsibility this actually meant for him, personally,” says Brandi, who describes the Nelson Tenths case as “an evolution”.

“We didn’t know in the High Court that we were going to get tossed out and that we’d have another chance through the Appeal Court; we didn’t know in the Appeal Court that Dad would get standing to take it through to the Supreme Court. Year after year we lost hope in the justice system, we saw the toll it took on the whānau, and we watched our uncles and aunties die not knowing what would happen to the case. Dad has lost most of his siblings now – all of these things have been significant to us.”

Brandi was just a child when the family discovered they had substantial land interests in the Nelson Marlborough region and, after her mother joined the Wakatū Incorporation Board in 1977, she began to learn more.

“We understood that a significant deal had taken place, that a very significant commercial opportunity had landed on our back doorstep with the return of the remnants of the Nelson Tenths to Māori ownership. I would have been 12 at the time and for me that was like we’d won Lotto.”

But the elation soon soured.

“As we started learning the history, it became obvious that there’d been a lot of breach and a lot of grievance, and we started to understand our tūpuna who had been alienated from their lands, lost their lands or been treated really badly.

“There was so much abuse. I recall our kuia who was put into a mental asylum because she wouldn’t give up her land. Other relatives tell us that in winter, Motueka was really wet, flooded and muddy and, in summer, there was drought. There were Nelson Tenths that should have been set aside for us yet we were living in the worst conditions possible.”

The emotional toll has been immense – but Brandi says that’s what keeps them fighting.

“We are trying to acknowledge the devastating circumstances our tūpuna lived in, making sure that we never have to suffer it again.”

It has felt mostly like an uphill battle, but Brandi couldn’t be prouder of the way her father Rore has led the charge – over decades. What keeps him going?

“Dad’s always had that commitment to the whenua. That’s just his natural modus operandi and he knows he has to do this for future generations to prosper from what our tūpuna lost. He’s not in the grievance mode that we used to be in. He’s all about righting the injustice and ensuring our mokopuna have the inheritance that they’re entitled to, the land interests and the money that is due to us all. He also knows that by doing this, by setting a precedent, he is helping potentially many other iwi.

“Dad sees this as his contribution as a rangatira – he genuinely understands the importance of us being rangatira on our own whenua.”

So what might the future look like for the Staffords and all those fighting for the return of the Nelson Tenths?

“Dad has always said that the Crown, the legal system, is about power and money, but for us it’s about whakapapa. We have a totally different world view to the Pākehā system.

“It’s really tough because the mechanisms of the government have torn us apart, we can see how colonisation has driven a wedge. My hope is that we find really strong ways to use rangatira and a peaceful approach to how we’re going to manage the asset, so that we will be really great examples of what is good for Māori will become good for all New Zealanders.

“Nelson Marlborough will benefit so much from us being landowners because we won’t sell out – that’s our whenua, our whakapapa, and our tūpuna. That’s our mokopuna and our tamariki.”

“Talk with your kaumātua — your nannies, toro, aunties, uncles, and cousins. Take the time to sit, listen, and listen some more, and kōrero when you can. Don’t take these moments for granted; in the blink of an eye, whānau can come and go, and with them, the stories and connections.”

“Talk with your kaumātua — your nannies, toro, aunties, uncles, and cousins. Take the time to sit, listen, and listen some more, and kōrero when you can. Don’t take these moments for granted; in the blink of an eye, whānau can come and go, and with them, the stories and connections.”

Our commitment to hold the Crown to account to make good on the Nelson Tenths weaves together many strands of work.

Our commitment to hold the Crown to account to make good on the Nelson Tenths weaves together many strands of work.

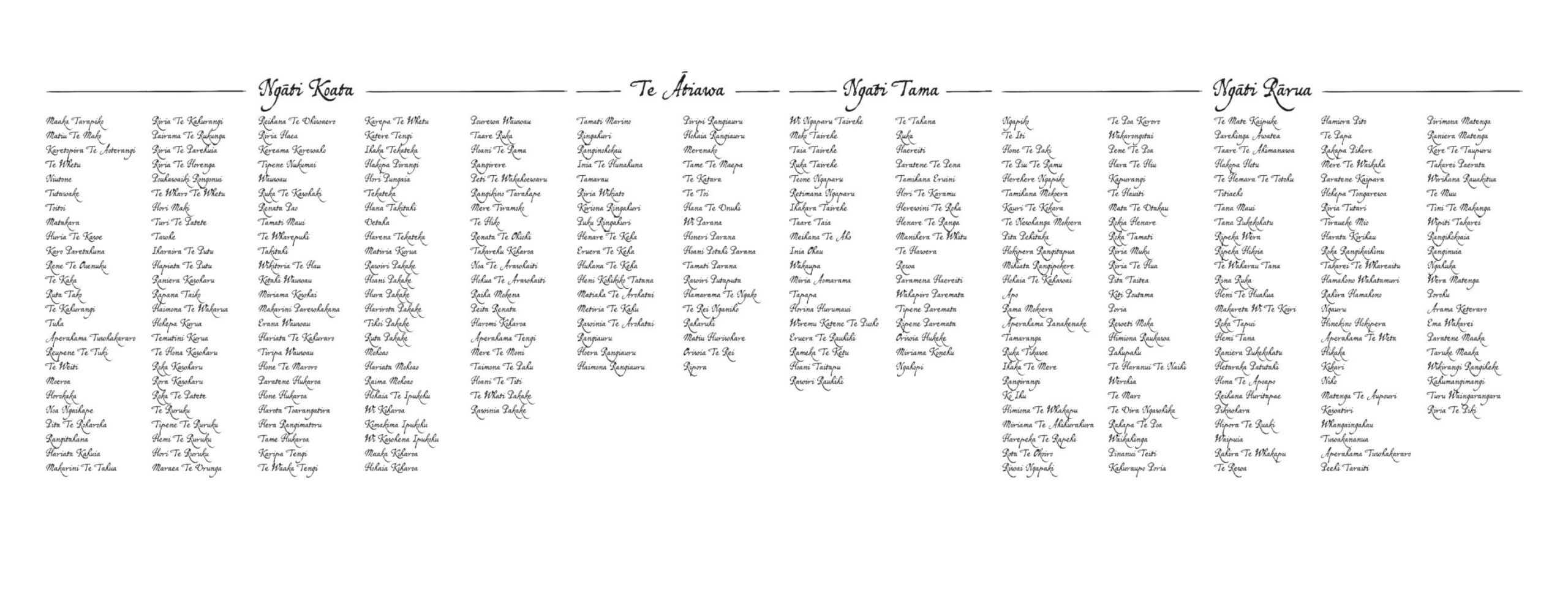

Whakapapa to me is our indigenous way to understand how the world is. It is inherent to who we are as Māori. It is our line we trace back that connects us to everything in the natural world. For me, whakapapa ties me to my hapū-based identity as Te Ātiawa and Ngāti Koata. It is a reciprocal relationship with all that is around us – we belong to the land, the river and the seas and it is our responsibility to protect and nurture it for mokopuna to come.

Whakapapa to me is our indigenous way to understand how the world is. It is inherent to who we are as Māori. It is our line we trace back that connects us to everything in the natural world. For me, whakapapa ties me to my hapū-based identity as Te Ātiawa and Ngāti Koata. It is a reciprocal relationship with all that is around us – we belong to the land, the river and the seas and it is our responsibility to protect and nurture it for mokopuna to come.

Ramari lost her home, her livelihood and her land and was ultimately held in the asylum for three years before being released.

Ramari lost her home, her livelihood and her land and was ultimately held in the asylum for three years before being released.